July 30, 2025

“Fiery Mary” & St. Elijah: Serbian Folk Saints Who Preside Over Summer’s Dangerous Heat

In Serbian Orthodox-informed Dual-Faith or Dvoverovanje, the period leading from the end of July to the beginning of August is a hazardous time. For rural folks in Serbia and elsewhere in Eastern Europe, it’s an intense time of arduous physical labor to process the harvest. It’s also a spiritually precarious time where the goal is to avoid the unwanted attentions of the pair of folk saints known as “Fiery Mary” (Ognjena Marija) and her “brother,” Sveti Ilija/Saint Elijah. Searing drought or a dangerous hailstorm sent by either of them can destroy the as-yet-unharvested crops.

Soaring temperatures at this time of the year, whether in the Balkans or the Midwest USA (the greater Chicago area has been roasting the past couple of weeks with heat indices past the 100° F mark), can certainly augment a collective sense of anxiety. Serbian folk beliefs pertaining to this pair of “Fire Saints” takes on a whole new level of alarming significance in this age of undeniable climate change and globally destabilized weather patterns, one of whose manifestations is the preponderance of out-of-control wildfires that last for months at a time.

a slavic sky goddess in disguise? the folk saint of “fiery mary”

A cursory look at the folklore surrounding “Fiery Mary” and Saint Elijah can translate into fascinating case studies of much older, fiercer, earth-spirituality-centric Powers subsumed into the Dual-Faith visual representation of Byzantine iconography. The fixed date of July 30 (per the Julian calendar) marks the Feast Day of Ognjena Marija. As seen in this 15th-century Russian Orthodox icon below, her tell-tale red robes, hexafoil fire motifs, and her stern visage give her away in Orthodox icons, signifiers that are consistent in color symbolism and artistic form from Serbia all the way northeastward to Russia.

As is the case with many other Slavic folk saints, the details from her official hagiography are scant. Sveta (“Saint”) Marija, who also goes by the name Marina, is referred to in Serbian catechetical lore as a Velika Mučenica—a “Great Martyr.” She hailed from the ancient Phrygian city of Antioch. She was put to death, supposedly for rejecting Pagan suitors, sometime during the reign of Emperor Diocletian (284-305 C.E.). The official story doesn’t have much else to say.[1]

Fortunately, the folk beliefs surrounding her abound in details that speak of a unique, perhaps mythologically unprecedented, Slavic sky goddess. She’s said to be the “sister” of the Old Testament prophet, Elijah. Sharing his quick temper and fondness for fiery cataclysms as a default response to human immorality, she’d gladly set the planet ablaze.[2] She is also said to use a heavy sledgehammer(!) to punish wicked people, smite devils, as well as hurl lightning, skills she shares with her “brother” and which certainly put us in mind of the Slavic thunder god, Perun. She punishes dishonest women by cursing them with infertility.

In rural areas of Serbia, various taboos rule her feast day and people know better than to do any serious chores—especially labor out in the fields. It’s best to stay indoors, period. And for women, that means no spinning of wool for use in the winter months to come, lest they draw the fiery ire of Ognjena Marija.

saint elijah the thunderer: avatar of perun

The Feast Day of Fiery Mary’s “brother,” Sveti Ilija Gromovnik/Saint Elijah the Thunderer, arrives two days later, on August 2 (Julian calendar; the Gregorian date is July 20). As the star Sirius makes its heliacal rising, bringing with it the hottest weather of the season, Sveti Ilija Gromovnik arrives in his chariot of fire, reminding us that the old Slavic thunder god, Perun, is remembered, honored, and more than a little feared in the guise of this Old Testament biblical personage.

Where I live, it does seem to almost always thunderstorm on August 2. From the time when I was a little girl to well into my adolescence, I would listen with rapt attention during thunderstorms to my mother’s tales of bad things that befell her neighbors in her hometown of Užice, Serbia—people who were punished at this sacred time of summer’s intensity. I heard stories of peoples’ orchards set ablaze in an instant during freakish storms and other sudden forms of loss incurred for violating the taboos of Sveta Ognjena Marija and Sveti Ilija.

It was even taboo, I learned to my astonishment, to make the Sign of the Cross during a thunderstorm! Sveti Ilija doggedly pursues the Devil around the world. Severe thunderstorms and lightning strikes occur when the fearsome saint, thundering past in his chariot, hurls his bolts like lances, hoping to zap the elusive Devil once and for all.[3] The cunning Devil knows that the normally effective apotropaic gesture of making the Sign of the Cross suddenly has no effect for the scared human hoping to keep evil away. Ever the opportunist, the Devil would like nothing better than to use a frightened child in a thunderstorm as a human shield. Making the Sign of the Cross can send the wrong signal—the Devil is hiding behind me! The “Thunderer” is pitiless and has no qualms with the concept of collateral damage ensuing from his righteous work. Thus, if Sveti Ilija were to hurl a lightning bolt, the child and not the Devil would be struck!

Eight-year-old me was horrified at the thought of being an unintended target of Saint Elijah’s wrath; during storms, whether at home or at school, I made sure to stay away from windows so as to not be seen by the saint passing overhead in his chariot of fire. And no matter how loudly the peals of thunder boomed and how frightened I became as a result, I never, ever made the Sign of the Cross to allay my fears and ask for Jesus’ or the Virgin Mary’s help in the moment. It was just too risky a move.

“If Ognjena Marija and Sveti Ilija had their way, the planet would be burned to cinders,” my mother would tell me, her eyes wide with alarm. “Totally destroyed! They love fire and will stop at nothing to punish evil-doers!”

Wow, the whole world! Those two mean business! My young imagination visualized horribly burned pizza crust and then magnified that a bazillionfold to calculate, in my mind, the scale of what the fiery destruction of the world would entail. It occurred to me that Saints Fiery Mary and Elijah seemed to be more powerful than God himself, who apparently chilled out considerably after that Great Flood business, at least according to what the Dominican nuns in my Chicago Catholic elementary school taught me. Jeepers!

As an adult, I’d say it’s quite clear that reverence for Saint Elijah took over the widespread cult in Slavic lands of the god of thunder and justice, Perun. A well-known pan-Slavic epithet for the god, as we’ve seen with the saint who arrived on the mythological sceen centuries later, is Gromovnik: “Thunderer.”[4]

We learned that the World Tree in the Slavic cosmos is an oak, and it’s in the top-most branches where Perun, in eagle form or accompanied by an eagle, likes to perch before setting out in his chariot to cause storms that ensue from engaging in combat with his serpentine enemy, the god Veles, Lord of the Underworld, who is often coiled at or beneath the World Tree’s roots. This is where my mother’s stories stem from: during the Christianization of the Slavs in the late ninth to the late eleventh centuries, Veles easily became transformed into the Devil,[5] and the early Christian Slavs saw in the iconography of Saint Elijah the form that Perun would take as all the elements were there: thunder, the chariot of fire, and the hurling of divine wrath in the form of lightning bolts.

Bulgarian icon of Sveti Ilija, St. Elijah

Was Perun the most important god worshiped by all Slavs before the conversion period began?[6] In the resurging Slavic Native Faith communities springing up in Eastern Europe today, Perun receives universal praise as the chief deity—he’s much more in the modern Rodnover consciousness than merely a god of storms. The centuries-old religious craft of carving god-poles as images of the gods meant to receive devotional offerings has been steadily making its way into public sites of worship again, from Poland to the Czech Republic to Croatia and Serbia to Ukraine and Russia.[7]

Kipa or “god-pole” of Perun at Perun na Učka, Croatia. Photo courtesy of Savez Hrvatskih Rodnovjeraca, (c) 2013. Used with permission.

As the Serbian folk observances show, these folks saints and the gods who preceded them are dangerous and necessary, governing the tightly woven skeins of life and death, being and non-being, past and present. The destructiveness of Ognjena Marija and Sveti Ilija/Perun showcase the precariousness of life: a lightning-spawned wildfire can and does devastate late-summer crops in the fields. It does destroy homes. We approach these dread and majestic personages, if we know what’s good for us, with a generous helping of humility.

watery pacification courtesy of the magdalene: Blaga Marija

Mary Magdalen icon from my own altar.

Perhaps if Sveta Ognjena Marija and Sveti Ilija had their way, the planet would, indeed, be engulfed in flames. But in the Serbian calendar, relief from destruction arrives two days after Saint Elijah’s Feast Day with the Feast Day of Elijah’s other “sister,” Blaga Marija, or “Mild, Benign, Gentle Mary.” She is equated with Mary Magdalene in Serbian Dual-Faith Tradition and she switches the Elemental focus from destructive Fire to healing Water.

In terms of the agricultural cycle, there’s a Serbian saying that goes: “Od svetog Ilije, sunce sve milije.” Translated into English (losing the clever rhyme scheme in the process), it means “From Saint Elijah’s Day onwards, the sun becomes more gentle.” If Ognjena Marija and Blaga Marija are two faces of the same primordial Slavic sky goddess, as some scholars suggest,[8] the switch from Marija’s ognjena (“fiery”) nature to her blaga (“benign”) one could herald the seasonal transition from summer to the first stirrings of autumn.

Sveta Marija Magdalena is first and foremost a protector of women. Serbian Orthodox Christians pray to her for healing, especially concerning reproductive issues. On August 4, her Feast Day, people make pilgrimages to one of many sacred springs and wells, found flowing beneath or adjacent to churches, that are named after her throughout Serbia. The devout seek holy water to anoint themselves with as well as to consume, either unceremoniously or in the context of a bajalica’s prescribed healing ritual. In rural communities, on the day of Blaga Marija, the taboos against laboring in the fields and chores involving the spinning of wool and other “women’s work” apply.

adapting the lore of the saints for today’s seekers: Suggested Spiritual practices

The most obvious adaptations of celebrating these folk saints’ feast days today entail rounds of spiritual cleansing, by fire and by water, respectively. On the dates of July 30 and August 2, I ask Saints Fiery Mary and Saint Elijah to purge and purify me, physically and spiritually, and to clear out of my life that which has served its purpose. I prefer to conduct my spell work at my indoor wood-burning fireplace or outdoors at my backyard fire pit.

When Blaga Marija’s Feast Day comes around, I enjoy taking spiritual baths to bring sweetness into my life. I’m also fond of excursions to nearby Lake Michigan, seeking out my favorite lonely beaches wherein I can meditate on the profound powers of Elemental Water. I tend to drink the Holy Water that I obtain at my local Serbian Orthodox monastery as a health tonic also. It’s also a traditionally appropriate activity to honor each saint on their Feast Day by cleansing their icons with Holy Water and adorning them with sprigs of fresh rosemary, hyssop, and basil—the trifecta of apotropaic herbs in Serbian folk magic.

Photo of icon of Sveta Marina with devotional plant offerings (basil, roses), New Gračanica Serbian Orthodox Monastery, Third Lake, IL. (c) Anna Urošević Applegate 30 July 2024. All rights reserved.

[1] Bandić, Narodna Religija Srba u 100 Pojmova, 214.

[2] Any devotees of the Egyptian goddess Sekhmet will surely recall the myth known as “The Destruction of Humanity,” wherein Ra dispatches Sekhmet to incinerate the human race as punishment for wickedness.

[3] Marjanić, “Dragon and Hero or How to Kill a Dragon,” 129.

[4] Ivanits, Russian Folk Belief, 29.

[5] Marjanić, “Dragon and Hero or How to Kill a Dragon,” 129.

[6] Dvornik, The Slavs: Their Early History and Civilization, 48.

[7] Ivakhiv, “The Revival of Ukrainian Native Faith,” 230.

[8] Bandić, Narodna Religija Srba u 100 Pojmova, 215.

july 4, 2025

locus of slavic magic: the Water Mill

Given its central importance in providing physical sustenance and spiritual purification, water looms large in the Slavic mythic consciousness. As an element, water serves as the permeable boundary demarcating “this” world from “that” one of the Otherworld: every well, holy spring dedicated to a saint, river, lake, and seashore can play host to a tutelary vodeni duh or grouping of vodeni duhovi. The two most widely known types of water spirits are the male vodenjak (the root of voda means “water” in most Slavic languages) and the female rusalka.

Also variously known as a vodeni čovjek (“water man” in Croatian), nečastivi (“evil one” in Serbian), or vodianoi chert (“water devil” in Russian), the vodenjak is almost universally regarded in the Slavic world as a dangerous being whose chief aim is to drown people.[1] Lacking the beauty of his female counterpart as well as her ability to switch habitats from water to trees, the humanoid-appearing vodenjak is thought to be ugly, green, bloated, bearded, scaly yet shaggy, and slimy. He largely stays confined to his own or neighboring waters, emerging no farther on land than the riverbank or the water mill, if there is one nearby.[2]

However, he can conjure a glamour about himself to appear as a handsome mortal man if his objective is to whisk away a beautiful human woman who captures his fancy. He is thought to be fiercely strong, so much so that escape from his grip is impossible. A century ago, peasants in Russia’s Orel, Tula, and Kaluga provinces claimed to glimpse sightings of fantastic underwater crystal palaces where the vodianoi held court among their own kin and the ranks of the humans who died by drowning.[3]

Numerous villages throughout the Slavic world have their own repertoires of legends about the vodeni duhovi and how to avoid being drowned by them. In eastern Serbia’s Bor District, near the town of Donji Milanovac, two of the main cautions include never mentioning the phrase “water spirit” for fear of invoking him—the epithet of onaj stari, “that old man” is used instead—and never answering if one hears one’s name being called outdoors three times aloud at night, as this means the nečastivi is attempting to cast his net to drown a person. Other dangerous behaviors to avoid include gazing at your reflection in the water, as this enables the nečastivi to target you. Never make the mistake of taking a riverside nap, whether on the bank or even on a moored boat, as this can tempt the vodeni duhovi to dance their kolo around you and entrap you in their world.[4] Ethnologists in the field have recorded these kinds of accounts in the month of July in particular—the month in which the nečastivi is thought to be most active.[5]

Places where drownings had occurred were considered “unclean” and shunned, especially at night. In general, the learned habit of getting out of the water and avoiding swimming, fishing, and bathing in rivers and lakes at the taboo times of noon or after sunset were considered the most effective strategies of dodging the vodenjak’s attention.[6]

But, just as with those for whom forming a pact with the Devil sounds appealing, there are always those who deliberately courted the vodeni duhovi for favors in exchange for their human souls. Successful fishing was one motivation. Another motive, sought by women only, was for the outcome of obtaining tremendous powers in witchcraft. That could only be obtained through sexual congress with the vodenjak. The water spirit’s sexual appetite is said to be insatiable.[7] The price to be paid for this strange coupling is high: it might be the death of the would-be witch’s husband, if she is married, or her fertility. The ultimate payment of death by drowning is reflected in the Serbian proverb of “Došao Džavo po svoje”—“the Devil came for his own.” In the not-too-distant past, attempts to recover the bodies of drowning victims were thought to anger the vodenjak, as he wanted to hold onto his rightful “prizes.” Bruises on the victims’ bodies were interpreted as signs of struggles with the fearsome strength of the water spirit.[8]

Aside from successful fishermen and witches, another demographic suspected of having entered into pacts with the vodeni duhovi was the village miller. In fact, the miller was often regarded as a sorcerer for having a friendship with the local vodenjak. It was known that, as with the construction of the bania or bath house in East Slavic lands, a rooster (ideally black) would have to be sacrificed at the threshold upon the construction of a water mill. Millers were known to continue to make offerings at least annually in the spring if not more frequently throughout the year to keep the local vodeni čovjek pacified. Vodka, bread and salt, tobacco, ram and horse heads/skulls, or entire slain black pigs were thrown into mill streams and offered to the water spirit.[9] Smooth operations at the mill and ease in catching multitudes of fish were surefire signs of a happy, well-placated vodeni duh.

[1] Ivanits, Russian Folk Belief (New York: M.E. Sharpe, 1989), 70.

[2] Noah Charney and Svetlana Slapšak, The Slavic Myths, (London: Thames & Hudson, 2023), 199.

[3] Ivanits, Russian Folk Belief, 72.

[4] Conrad, “Male Mythological Beings Among the South Slavs,” 6.

[5] Dušan Bandić, Narodna Religija Srba u 100 Pojmova [Serbian Folk Religious Beliefs as Surveyed Through 100 Concepts], (Nolit, 2004), 159.

[6] Ivanits, Russian Folk Belief, 72.

[7] Ristić, Balkan Traditional Witchcraft (Los Angeles: Pendraig Publishing, 2009), 182.

[8] Ivanits, Russian Folk Belief, 73.

[9] Ivanits, Russian Folk Belief, 73.

JUne 28, 2025

vidovdan: feast day of the god svetovid

Whether they’re viewing it from a religious or from a secular/political perspective, Serbian folks register the date of June 28 as something extraordinary: it’s the fateful date, in 1389, when the Serbian emperor Tsar Lazar Hrebejanović’s armies fell to the invading Ottomans led by Sultan Murad I at the Battle of Kosovo. There is curious folklore that showcases the overlap between the fairy women, vile (VEE’-leh), and the cult of the ancestors. In the stories I was told as a child by both my parents and by teachers in my Sunday Serbian school, several vile chose men from Serbian noble families to be their mortal husbands. On the eve of the Battle of Kosovo, the vile roamed the field of battle (Kosovo Polje), keening and wailing, warning of the deaths of Tsar Lazar and his knights. A handful of the latter category observed the vile; the fairy women gave them red wine to drink, transforming the warriors into dragons who would someday avenge the deaths of Tsar Lazar and his retinue, all of whom became canonized as martyr-saints in the Serbian Orthodox Church.

serbian vidovdan folklore and the plant medicine of pimpernel

The Slavic god Svetovid/ Świętowita/ Su’vid is a deity of light, divination, abundance, and war. When and why His cult was grafted onto a supposed fourth-century Sicilian saint named Vitus, who is petitioned for protecting people against dog attacks, is quite a mystery. (Even the Catholic Church admits the man’s hagiography is pure legend.[1]) Perhaps it’s because the saint’s feast day in the Catholic Church, June 15, replaced the earlier Pagan celebration of Svetovid. In the Julian calendar observed by the Orthodox Church, the feast day of St. Vitus (“Vid” in Serbian) is today, June 28.

Intriguingly, in South Slavic folk magic, it’s the Slavic god and not the Catholic saint who is addressed in divinatory spells and healing magic done on this day, magic which is focused on peoples’ eyesight and on the ability to psychically “see.” On this day, the first magical act is to rise very early in the morning and pluck the plant whose folk name is Vidovčica trava, “Vid’s grass,” which is comprised of both varieties of pimpernel: scarlet (Anagallis arvensis) and blue (Anagallis foemina). Those flowering plants are placed in a vessel containing spring water and folks ought to wash their faces with it in order to prevent optical diseases.

Near the Fruška Gora mountain in Serbia’s far northern Vojvodina region, ethnologists in the field have recorded this variation of the Vidovdan face-washing ritual among carpenters and woodworkers by trade: As the men wash their faces, they say: “Oj, Vidove! Vidovdan! Štoja očima video, toja rukama stvorio!” / “Oh, Vid! Vidovdan! All that my eyes see, my hands may create!”[2] By magical inference, then, their talents will have no limits.

A slight variation on this spoken charm, now involving a mother and a daughter, has been recorded further northeast in the same Serbian region, in the village of Banatski Dvor. A mother takes her daughter out to the fence post that borders their field; they wash their faces and say together: “Vido, Vidovane! Što god očima vidim, sve da znam raditi.” / “Vido, Vidovane! All that my eyes can survey, I will know how to work.”[3] In other words, Vid will magically endow the women with whatever knowledge they need to be able to carry out their work. As they survey a limitless horizon, so too will their skill sets be limitless.

The colors red and blue, based on the pimpernel flower varieties, repeat themselves in other magical acts, carrying symbolic currency. This leads some scholars to speculate that red and blue could very well have been the cultic colors associated with the worship of the God Svetovid/Vid, at least among the South Slavs (the god’s cult was strongest amongst the West Slavs). In a dream incubation ritual recorded in Bosnia by single women looking to dream of their future husbands, both varieties of the pimpernel flowers are placed under the pillow. The woman drinks a cup of rosehip tea (more red symbolism) while brushing her hair before her bedroom mirror. She says the following before immediately going to bed:

“O moj Vide, Viđeni,

O moj dragi suđeni,

Ako misliš jesenac da me prosiš,

Dođi večeras, u prvi sanak na sastanak.”

“O my Vid, the All-Seeing,

O my dear fated one,

If you’re thinking of proposing to me in the autumn,[4]

Come tonight instead, we’ll rendez-vous in my first dream.”[5]

Again, as the first line reveals, the Slavic god is addressed directly (the future husband then is addressed from the second line onward), and His functions related to divination and His ability to see in the four cardinal directions has remarkably survived intact in South Slavic folk memory more than a millennium after Christianization.

celebrating svetovid and asking for his counsel

The variants of spelling in the god’s name can denote two different but complementary etymological meanings: in Common Slavic, the prefix “sve-” and its variants translate to “all,” “the totality” of something. However, the distinct prefix of “sviato-” or “swieto-” means “holy, sacred.” The variants of the suffix “-vid,” “-vit,” “-wita,” all derive from the verb videti, “to see.” Hence Svetovid is the “All-Seeing” or “World-Seeing God” and Sviatovyd is the “Holiness-Seer.” Either way, the god’s function of divination is inherently emphasized. My divination and my devotional rituals to Svetovid always include an outdoor fire and offerings of mead to Him. I feel His Presence at my backyard shrine quite strongly in the summer months.

This wooden statue of Svetovid was something I purchased online in 2017 from the amazing, archaeologically educated artisans behind OIUM, who are based in Kyiv, Ukraine. These and other images of Him are derived from the so-called “Zbruch Idol,” a fantastic ninth-century Slavic religious artifact carved out of limestone that was excavated from the Zbrucz River near Liczkowske, Poland (present-day Ternopil Oblast, Ukraine).

Svetovid resonates in my heart strongly. I have never visited the beautiful medieval Polish city of Kraków, but I have toured via the Internet its main museum, which now houses the Zbruch Idol. I’m always moved to tears when I sit in contemplation of this holy artifact. I also sobbed out loud in April of 2022 when a friend and I went on opening night to see the film The Northman (Robert Eggers, director). Scenes of the raids on the Slavic Rus’ villagers, the enslavement of the Rus’ women, the murder of the villagers, and the scene masterfully played by Björk as the temple of Svetovid priestess (photo below) overwhelmed me.

I felt the collective experiences of my Slavic ancestors, and even though the film shows “Polytheist-on-Polytheist” violence, I knew at some level in the scene with the desecrated temple of Svetovid that I was actually mourning the desecration of Svetovid’s most famous temple complex called Arkona. The missionaries of the Christian Danish King Valdemar I destroyed the Arkona temple and slaughtered its priests in June of 1168.

So perhaps this historical fact is the real reason why my Serbian heart feels so heavy on Vidovdan: the Christian violence against the Pagan Slavs, not the medieval Serbian empire’s tragic defeat by the Ottomans on June 28, 1389. Thankfully, Svetovid’s devotees continue to grow throughout the Slavic Diaspora. We are coming out in full force to praise this powerful god, as it is right and just to do so.

spell to invoke svetovid’s protection

On a round piece of linen cloth approximately nine inches in diameter, place one part of each of the following dried herbs: St. John’s Wort, rosehip, sweet basil, rosemary, angelica root, geranium, wormwood, yarrow, juniper. Lastly, add one fresh garlic clove (minced).

Gather the edges of the cloth and bundle upwards, then take a white or red cotton string or piece of yarn and tie the bundle together with the words: “Svetovid rides on His white horse and puts to flight the Unclean Force.”

Carry the bundle with you on your person, hang it from the rearview mirror of your car, place it under your pillow, or tuck it into your desk drawer at the office.

Slava!

[1] Catholic.org, “Saint Vitus,” https://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=140.

[2] Bandić, Narodna Religija Srba u 100 Pojmova, 338. The translation is the author’s own.

[3] Bandić, Narodna Religija Srba u 100 Pojmova, 338. The translation is the author’s own.

[4] The most favored time of the year for marriage among the South Slavs. It’s a time of abundance and celebration, as the harvest has ended.

[5] Bandić, Narodna Religija Srba u 100 Pojmova, 339. The translation is the author’s own.

June 12, 2025

Reviewers have good things to say about slava!

I’m completely overjoyed to see how my forthcoming Llewellyn Worldwide, Ltd. book, Slava! Slavic Paganism and Dual-Faith Folk Ways (release date: 2/8/2026 and now available for pre-order!) is resonating with its cadre of advance-copy reviewers, including luminaries in contemporary Paganism, Hoodoo, and Heathenry. Author Alaric Albertsson has this to say about my book:

“For years, many contemporary Pagans have drawn their inspiration from Germanic, Classical, or Celtic cultures. Now, Anna Urošević Applegate presents the traditions of Slavic Polytheism in Slava! Slavic Paganism and Dual-Faith Folk Ways. Her book begins with an exploration of the native, Pagan origins of the Slavic faith, and goes on to examine how this later became coupled with Christianity to survive as a Dual-Faith Tradition. Applegate includes rituals, prayers and even recipes to provide a truly immersive experience for anyone who would like to learn more about the cultural traditions of eastern and central Europe. I found the book to be both informative and thought-provoking, and I highly recommend it.”

—Alaric Albertsson, author of Wyrdworking and A Handbook of Saxon Sorcery & Magic

More Praise for Slava!

“Slava! is a thoughtful work of cultural ambassadorship, merged with spiritual memoir, along with a good helping of anthropology, well-vetted folklore, history, and Magick, capped off by compelling storytelling. Within these pages you will encounter tree and plant wisdom, spells, ancestor veneration and considerations, environmental stewardship connections, rites directly from Slavic tradition and those created by the author, deities, fairy-lore, useful tools, and more. This polytheistic, earth-centered, and, at times, Otherworldly, tome looks at the past to pave a road to a lively and meaningful Slavic Magick practice of now and the forevermore.”

—Priestess Stephanie Rose Bird, author of Sticks, Stones, Roots, and Bones and Motherland Herbal

“Slava! is one of the most important books to come out of contemporary polytheism today. It fills a crucial gap in the literature available both to academics and, more importantly, to practitioners….Most importantly, Anna discusses syncretism, the blending of Christian and polytheistic practices that make up an all-too-often neglected aspect of contemporary living polytheisms, one that many polytheists are ashamed to discuss. This book is essential for anyone interested in the potent call of gods that predated Christianity by millennia. Anna highlights the thing that many contemporary polytheisms miss: our traditions evolved connected to spirits of particular places, particular peoples—and while anyone may honor the gods, learning about those origins can only deepen a person’s connection to the Holy Ones. I cannot recommend this book highly enough.”

—Galina Krasskova, PhD candidate, Theology, Fordham University; author of A Modern Guide to Heathenry and Living Runes

JUNE 8, 2025

the gods of june: Triglav and svetovid

Rusal’nalia Week culminates in today, Trinity Sunday. Also known as the Feast of the Holy Trinity, Pentecost, or Duhovi (Serbian for “Spirits”), today is the special day in Serbian culture when folks go to church to weave a bit of folk magic into their lives using the everyday plant medicine of tall grasses. The Divine Liturgy is long, painfully so, and it requires a lot of physical dexterity on the part of the officiating Bishop and the congregation, especially since kneeling on the marble church floor for extended periods of time is required. But the sacrifice in physical pain is worth it, as one by one, prayers and magical intentions are set in the fibers of grass as they’re woven together to create an individual venac, or wreath.

Clearly, this is a Pagan practice that the Orthodox Church in its centuries-long campaign to convert the Southern and Eastern Slavs couldn’t stamp out, so it wisely incorporated it into its ecclesiastical calendar, which is designed to align itself with the agricultural and animal husbandry cycles that inform the lives of country folk.

The symbol of the circle is tied to so many concepts, chiefly the Sun and the notion of the cycles of time, which find expression in Slavic Native Faith as the kolovrat and in virtually every Slavic culture as a circle-based form of folk dance. Throughout the former Yugoslavia and Bulgaria, the dance is called a kolo, for “wheel.” Among the East Slavs, the word is khorovod, etymologically linked to the Solar deity of Khors, Who is mentioned as being among Prince Vladimir’s courtly Pantheon in the tenth-century Russian Primary Chronicles.

The idea of celebrating a “Trinity” also predates the arrival of Christianity, as the Pagan Slavs—especially the South and West Slavs—honored a polycephalic Deity named Triglav, for His three heads or faces.

It’s likely that “Triglav” (“Three Heads”) is a euphemism as saying the name of the actual God was more than likely a taboo, especially when so much of this Deity’s lore—even in modern-day Slovenia—is chthonic, with devotional practices and documented spellcraft (for fertility of the fields) taking place in caves.

As I was working on the writing of Slava! Slavic Paganism and Dual-Faith Folk Ways exactly a year ago, at the Summer Solstice last year I had an incredible dream of Triglav that I actually believe was a visitation from Him, with me journeying to the Underworld in order for the meeting to happen. The Triglav statue in the above photo that I received as a gift from my cousin Neli in Beograd, Serbia several months later confirmed to me that He indeed visited me, as the hair and beard were identical to how He appeared to me in the dream.

Hence I believe the build-up to Solstice is a very powerful time of year to feel Triglav’s energies.

The other Slavic God I associate with June is another polycephalic Power: the four-faced Svetovid. We have documented spell work among country people in modern-day Bosnia and Serbia of appeals to Svetovid for success in one’s occupation and for optical/ eye health and the removal of eye diseases as taking place every June, specifically the dates June 15 and June 28, the days assigned by the Catholic and the Orthodox Churches, respectively, to a wholly fictitious Saint named St. Vitus or Vid. The Catholic Church, to its credit, admits the Saint’s hagiography is pure legend, at any rate, so it’s clear that Vitus/Vid was meant to displace the peoples’ reverence for Svetovid.

One of the fascinating aspects of working in the Dual-Faith tradition is having the ability, born of unmistakable clarity, to peel back the onion layers of Christian influence and get to a very Pagan core of things. So I have no qualms at all about going to Trinity Sunday service for the express magical purpose of praying and weaving my grass wreaths. For what is spell work but applied prayer? And I even have the chutzpah to then take wreaths made in a monastery and bring them home to adorn the heads of statues of my ancestral Gods.

A Prayer to Triglav and Svetovid

Slava, Triglava! Slava, Svetovidu!

Holy Ones, All-Seeing Ones,

Guides of the Slavic peoples,

Keepers of ancestral wisdom,

Keep me free of all baleful influences.

Bless my eyes and my heart to see

The truth of all peoples and situations,

Not what I wish them to be.

May Your swords cut away all illusions

And grant me the ability to stand unwavering

In truth and the peace that comes from it.

Bless my hands to do Your work in the world.

I honor You, Holy Ones, Eternal Powers,

And give great thanks to be able to open my

Heart and my life to deepen our connection.

And so it is!

Slava Rodu!

june 1, 2025

Rusal’nalia week Begins!

In the seasonal Dual-Faith calendar of Slavic countries that came to be outwardly spiritually colonized by the Eastern Orthodox Church, the week leading up to the great Feast of Pentecost is said to be the week of greatest power for the rusalki, the feared female-gendered water spirits (singular: rusalka) of Slavic folk belief. As a sign of them being at the height of their powers during this week of the year, rusalki–unlike their male water spirit counterparts of the vodanoi/vodeni duhovi–have the ability to leave their watery abodes of rivers and lakes and head far inland. They can be seen, especially by those born on a Saturday, dancing a kolo/khorovod in forest clearings or heard laughing and singing in trees.

Who are the rusalkI?

Hostile to humans, especially women, the rusalki punish those who trespass into their revels by driving them mad or making them physically ill to the point of death. Those unfortunate folks, in Serbian folk belief, are said to be “taken” by the rusalki.[1] Considered throughout all Slavic lands to be the souls of unbaptized babies or women or girls who drowned (in either case, they are the “unclean” dead), rusalki, despite their physically beautiful appearances that closely resemble their land-dwelling nonhuman cousins of the vile, are nevertheless regarded as another manifestation of the Nečistaja Sila—the “Unclean Force.”[2]

To this day in rural Serbia, protocols have to be followed, especially by women, for the entirety of Rusal’nalia Week to ensure that the rusalki stay away. Not only do women avoid bathing in rivers and their favorite local swimming spots, they don’t even come near the water, period. Nor do they court danger by napping outdoors. It’s also considered wise to avoid engaging in spinning, weaving, knitting, doing laundry, working around the house, and gardening for that entire week.

If those chores, especially ones done outdoors like gardening that would put you in the line of sight of the rusalki, can’t be avoided, the best insurance is to carry sprigs and roots of wormwood (Artemisia absinthium) on your person and have bunches of the herb on display throughout the house. This is the most apotropaic herb used throughout the Slavic world to keep the rusalki at bay.[3] Methods of rendering rusalki harmless include making the Sign of the Cross, proffering garlic, or enclosing yourself within a magic circle drawn on the ground. However, some women in East Slavic countries go the route of trying to appease the rusalki with offerings of linen hung in trees.[4]

The rusalka is certainly a more complex figure than her male counterpart of the vodenjak. Combining traits that apparently fuse the classical Greek mythological beings of the siren and the naiad with an indigenously Slavic forest spirit and with Christian folk religious superstitions about the dead who died unbaptized or unnaturally via drowning, the rusalka bridges the dualism that divides Slavic goddesses as being either forces of life (e.g., Vesna) or forces of death (e.g., Mara).

The rusalka is a dangerous being, associated with the “unclean” dead, yes, but her ability to leave her underwater domain for the land (at least during the spring and summer months) attests to her powerful, Goddess-given, life force–promoting critical function of bringing new life to vegetation. She transfers the magic of life’s inception, which occurs in water, from river or lake to forests and more importantly, to fields of grain.[5]

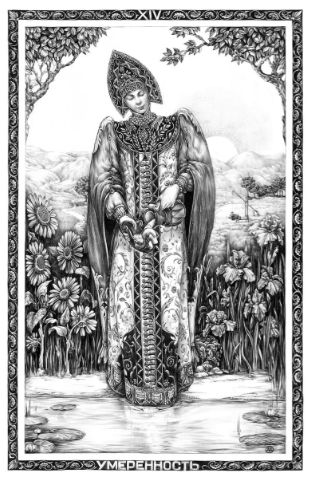

Singing to the hauntingly beautiful aria (“Song to the Moon”) in Act I of Czech composer Antonin Dvorák’s 1900 opera that bears her name, the rusalka captivates us as she carefully balances the waters of life and waters of death within her. In this regard, I think of her as a wholly Slavic version of the female divine being often depicted in the Tarot’s Major Arcana card of Temperance.

She provides us with much to meditate upon about the cyclical nature of reality and our own ways of marking our celebratory stations with each unfurling of the spiral. Slava!

[1] Dušan Bandić, Narodna Religija Srba u 100 Pojmova, 156.

[2] Linda J. Ivanits, Russian Folk Belief, 187.

[3] Bandić, Narodna Religija Srba u 100 Pojmova, 156.

[4] Ivanits, Russian Folk Belief, 75.

[5] Ivanits, Russian Folk Belief, 75.

May 20, 2025

The cover art for Slava!, which will be released by llewellyn worldwide ltd. in february 2026, has just been released!

Isn’t this art by Croatian artist Nataša Ilinčić just divine?! Here we have the Slavic World Tree with the complementary opposites of Perun in the branches and Veles as a ram-horned serpent on the ground. My book on Slavic Paganism and Witchcraft and the Dual-Faith (Dvoverovanje) tradition will be a 6″ x 9″ paperback with 360 pages. It reflects 17 years of my academic research, not just my lived experience at having been raised in Dual-Faith, which commingles Slavic Paganism with folk Orthodox Christianity, in my case Serbian folk Orthodoxy.

My good friend and fellow Witch and spirit-worker Fio Gede Parma wrote the Foreword. The tentative release date is mid-March 2026 and the cost is $22.99. It is apparently now available for pre-order on Llewellyn.com! Slava! / Glory!

may 14, 2025.

A Song for jarilo at the greening of the year

He canters towards us on this day,

Zeleni Jurej!

Who will be His Queen of May?

Zeleni Jurej!

Where Green George walks,

The fields will sprout.

Zeleni Jurej!

Let’s greet Him with our joyful shout:

Zeleni Jurej!